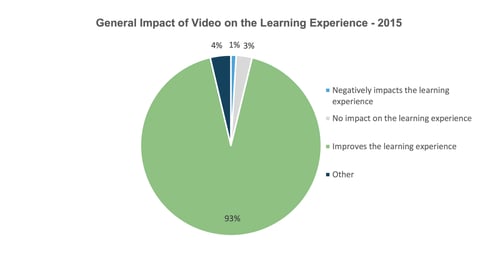

There is little doubt about the effectiveness of video as a tool for improving learning. As researchers noted in a report by Kaltura, a provider of a video technology platform, entitled The State of Video in Education 2015, educators overwhelmingly believe video improves the learning experience.

This is likely due, in no small part, to the fact that video has become a pervasive source of information consumption and entertainment for adults in the U.S. According to eMarketer, the average adult in our country spends more than 5.5 hours daily watching video content. Among the adult population, millennials are the most active video viewers of any age group – more than 92% of all U.S. millennial Internet users watch digital video.

User familiarity with video as a medium certainly reduces any resistance to form, and allows learning designers to take advantage of product experience standards that have already been established via other markets.

Thanks to the proliferation of smartphones, video creation has become both easy and flexible for almost everyone. This is reflected in the latest YouTube statistics, which show more than 300 hours of video being uploaded to the service every hour.

It’s best to think about learning video in the context of cognitive science – how humans process information. The research in cognitive theories for learning through multimedia shows we watch learning videos through two parallel channels: 1) a visual/pictorial channel; and 2) an auditory/verbal processing channel (Mayer and Moreno, 2003). Our goal in designing effective learning video is to get the most out of both the visual and the auditory channels. We want to prioritize and balance each of them in a way that optimizes the reception and processing of the information presented. Our challenge is that each of the channels has limited memory capacity, so it’s important to employ the following practices:

Signaling – Signaling can be done through the use of on-screen text or graphics to reinforce specific information. This directs the learner’s attention and highlights specific information s/he needs to process.

Segmenting – Segmenting refers to how we “chunk” information into appropriate sizes so learners have more control over how to process it. We can achieve this effectively by managing the length of videos, or by placing clear pauses or break points with a clip.

Weeding – Weeding refers to removing any unnecessary information from our videos. In our learning videos, we want everything – music, images, spoken words, graphics, and animation – to contribute as explicitly as possible to our learning goal. This allows learners to maximize their memory capacity for both visual and auditory channels, and to achieve the maximum amount of processing for effective recall.

Matching Modality – It’s important to combine and harmonize both the visual and audio channels, placing each type of information into the channel for which it’s best suited. An example of this might be showing an animation of a process on screen while narrating it. This uses both visual and audio channels to explain a process, and it gives the learner complementary streams of information to highlight features that can be processed in working memory. If we show an animation and merely reinforce it with on-screen text, we limit information to the visual channel and risk information overload and loss of cognitive efficiency.

Here are some key recommendations for creating successful learning videos:

Sweller, J. (1994). Cognitive load theory, learning difficulty, and instructional design. Learning and instruction, 4(4), 295-312.

Mayer, R. E., & Moreno, R. (2003). Nine ways to reduce cognitive load in multimedia learning. Educational psychologist, 38(1), 43-52.

Brame, Cynthia J. (2016). Center for Teaching. Vanderbilt University, n.d. Web. 20 June 2016.

2701 E Imhoff Rd.

Norman, OK 73071

405-673-5582

6125 Luther Lane, #416

Dallas, TX 75225

469-210-8204

careers@nextthought.com

videosales@nextthought.com

© Copyright 2019. NextThought Studios.